02:38 -

© EYESEEmag

They’re all painters who left their mark on the history of art, but the masterpieces they left behind hide a surprising fact. Monet, Degas and Van Gogh all had eyesight problems which prevented them from seeing clearly. But far from holding them back, their visual challenges made for even richer art.

It seems that painting when you don’t see very well can sometimes reveal a real gift. Each of these artists did it and managed to create a considerable number of masterpieces between them. Refusing to give up their passion despite their eyesight problems, they decided to nourish their art and transform what was viewed at the time as a handicap, into a real artistic strength. At a time when we could soon be wearing glasses that enable us to listen to music without headphones, we can only admire the mental strength of these artists, back when medical science was not as advanced as it is today.

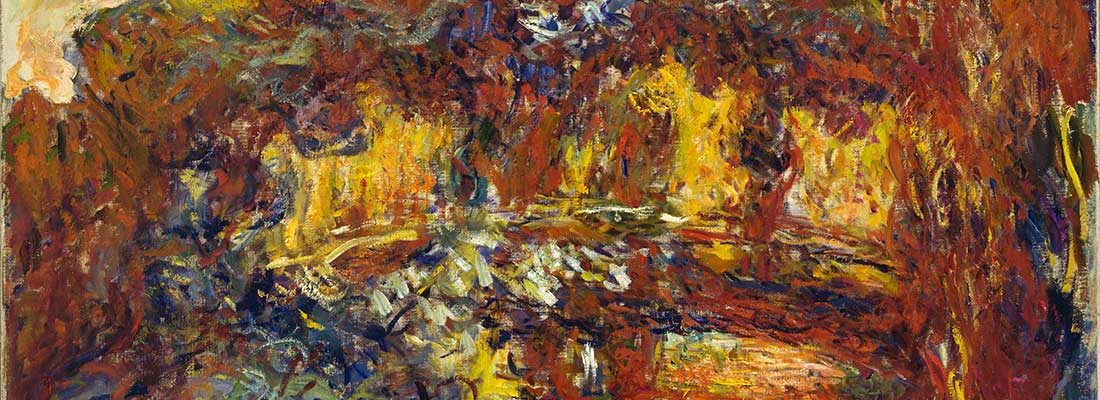

The celebrated impressionist worked mainly in blue and cool tones for many years. Yet, at the end of his life, his canvases were a riot of reds and yellows in an apparent about-turn. Far from being down to a change of style, it was in fact due to a change in perception. In 1912, Claude Monet learned that he had cataracts, a disease of the eye that seems to have left its mark on his work. By distorting the light coming into the eye, cataracts reduce the capacity to perceive blue and purple and accentuate perception of warmer colors. The painter could distinguish details less well, which impacted the finesse of his brush strokes: “my bad eyesight meant that I saw everything through a fog,” he wrote. “It’s very beautiful and it’s what I would like to be able to represent in my art.” Known for his tendency towards stubbornness, he continued to paint and refused to be operated on. Understandable, as at the time, any surgical intervention carried a real risk of permanent blindness.

To better understand how his eyesight problems changed his art, take a look at the two paintings below:

© Claude Monet, The Water Lily Pond, 1899

By the time he could no longer make out the color of his tubes of paint, he was forced to rely on memory and the precise order in which he stored them. By 1923 he was almost blind and finally gave in to pressure from his friend Georges Clemenceau and agreed to go under the knife, but only on his right eye.

© Claude Monet, The Japanese Bridge, 1922

Degas could barely see

An artist who at his peak could capture the beauty of dancers like no-one else, was obliged to evolve his art as his vision deteriorated. Suffering from a serious eye disease, Edgar Degas began to progressively lose his vision in 1870. But it was out of the question for him to slow down, so he decided to take up sculpture and pastels, leaving behind his oil work, which was too detailed for his poor vision. His art might have changed, but the genius remained.

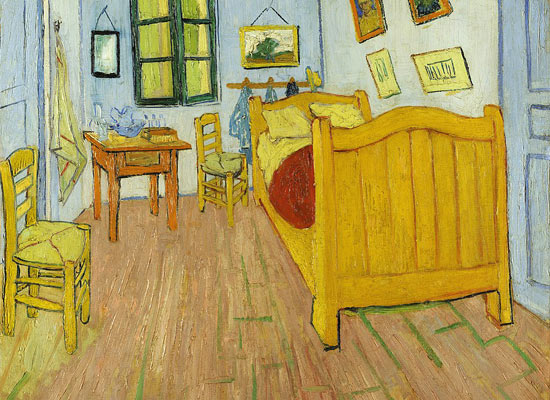

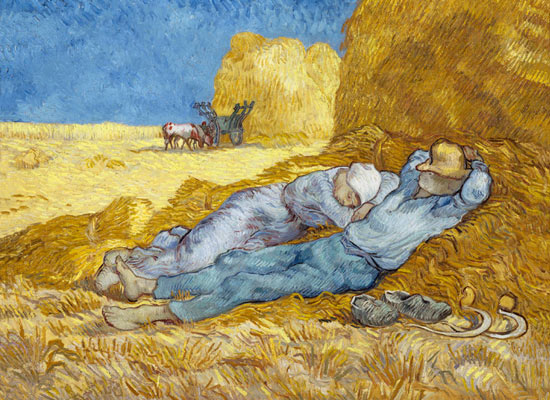

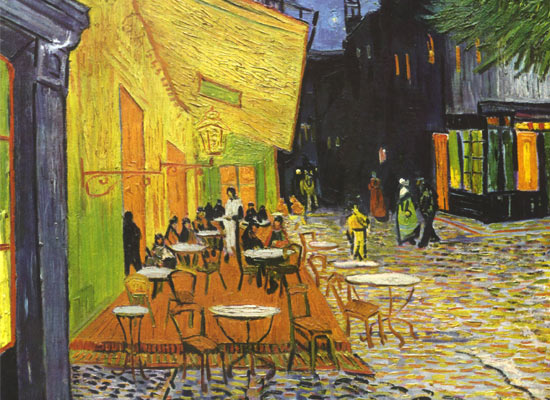

Van Gogh may have seen in tones of yellow

Known for his mental health struggles, the artist was far from seeing life through rose-tinted glasses. He is actually thought to have seen in yellow due to a condition called xanthopsia, a vision deficiency that causes the sufferer to see more yellow. His excessive consumption of absinth and abuse of digitoxin, a medicine prescribed by his doctor to treat his attacks of dementia, are thought to have contributed to the condition.

© Vincent Van Gogh, The House of Van Gogh in Arles, 1889

© Vincent Van Gogh, La méridienne ou La sieste (d_après Millet), 1890

© Vincent Van Gogh, Coffee terrace at night, 1888

No-one has yet managed to explain the secret behind the Mona Lisa’s soft smile, but her creator’s secret is out in the open. Just like Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci is thought to have had a squint, which may in part explain his talent.* The eye problem actually enables sufferers to better represent faces and objects in three dimensions, as well as depth in landscapes.

*According to a study led by Christopher Tyler, researcher at the University of London, published October 18 in Jama Ophthalmology journal.